Improving School Connectivity to Address Childhood Diabetes

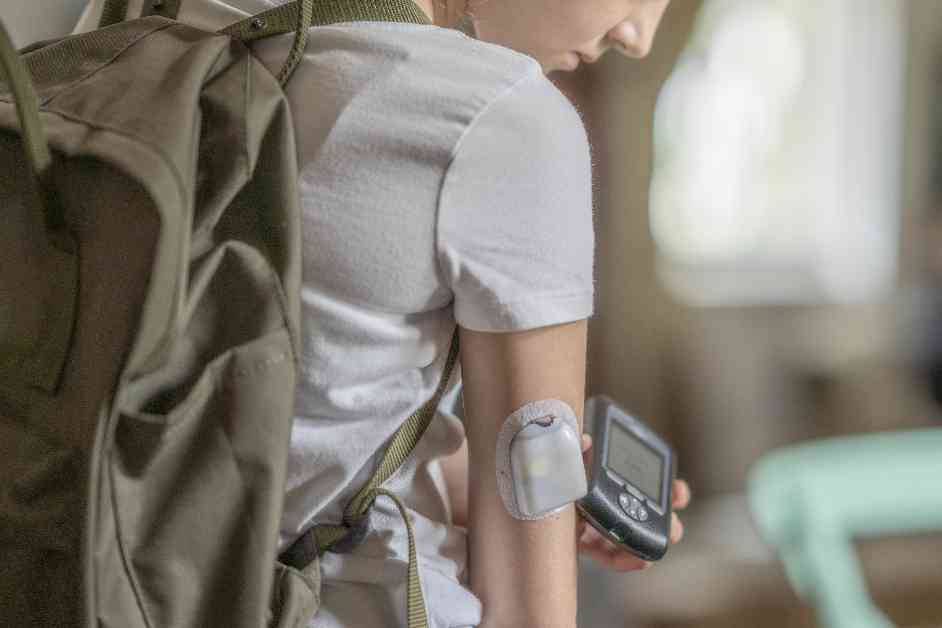

In the not-so-distant past, children with type 1 diabetes would make frequent trips to the school nurse for a finger prick to check if their blood sugar levels were dangerously high or low. However, the introduction of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) has revolutionized this routine. These small devices, typically worn on the arm, feature a sensor under the skin that transmits readings to an app on a phone or other wireless device. The app provides instant blood sugar level updates and issues an alarm when levels fall outside the normal range.

For these children, a blood sugar level that is too high might necessitate a dose of insulin—administered through an injection or by pressing a button on an insulin pump—to prevent potentially life-threatening complications like loss of consciousness. Conversely, a sip of juice could resolve a dangerously low blood sugar level, preventing issues such as dizziness and seizures.

In school settings, teachers keep an eye on students’ CGM alarms on their phones. However, many parents express concerns that a teacher might not hear an alarm in a noisy classroom, leaving the onus on them to ensure their child’s safety by monitoring the app themselves, even if they are unable to respond quickly.

Many parents advocate for school nurses and administrative staff to remotely monitor CGM apps, ensuring someone is vigilant even when the student is outside the classroom, on the playground, in a loud cafeteria, or on a field trip. Yet, numerous schools resist these efforts, citing staffing shortages and concerns about internet reliability and technical issues.

Julie Calidonio, a parent from Lutz, Florida, voiced her frustration, stating that the school district fails to grasp the urgency of the situation. Her 12-year-old son, Luke, who uses a CGM, has received minimal support from his school, with alarms often going unheard or unattended when his blood sugar levels plummet dangerously.

Taylor Inman’s daughter Ruby, a San Diego student diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 6, faced similar challenges. Despite wearing a CGM that alerts to abnormal blood sugar levels, the public school did not commit to monitoring the alarms through an app. Consequently, the Inman family acquired a support dog trained to detect abnormal blood sugar levels and transferred Ruby to a private school that remotely monitors the alarms.

These stories highlight the ongoing struggles faced by families of children living with type 1 diabetes in navigating the educational system. Despite the proven benefits of CGM technology in preventing health risks, schools’ resistance to remote monitoring remains a significant barrier to ensuring the safety and well-being of these students.

Legal Battles and Advocacy Efforts

In September, Calidonio lodged a complaint with the Department of Justice against the school district, alleging that their failure to monitor CGM devices violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This legal battle echoes a similar situation in Connecticut, where the federal prosecutor determined that monitoring a student’s CGM at school was a reasonable accommodation under the ADA.

Jonathan Chappell, one of the lawyers involved in the Connecticut cases, emphasized the importance of advocating for students’ rights. Despite legal victories in certain states, many families across the country continue to face challenges in getting schools to monitor CGM devices remotely. This discrepancy underscores the need for more widespread awareness and enforcement of ADA regulations in educational settings.

Expert Insights and Policy Recommendations

Health experts stress the critical role of CGM technology in managing type 1 diabetes, with the majority of young diabetes patients in the US utilizing these devices. While schools must balance student needs with staffing constraints, the American Diabetes Association updated its policy to emphasize the importance of allowing school nurses or trained staff to monitor CGM remotely if medically necessary.

Endocrinologist Henry Rodríguez underscores the importance of individualized care for diabetic students, acknowledging the challenges schools face in providing adequate support. Despite these challenges, advocates like Lynn Nelson emphasize the legal obligation schools have to meet students’ health needs, including remote CGM monitoring.

As the landscape of diabetes management in schools evolves, parents like Lauren Valentine, who successfully campaigned for her son’s school in Virginia to adopt remote CGM monitoring, provide a beacon of hope. These efforts demonstrate the power of advocacy in effecting positive change and ensuring the safety and well-being of students living with type 1 diabetes.

The integration of CGM technology in school settings not only enhances the quality of life for children with diabetes but also fosters a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. By leveraging technology, legal protections, and advocacy efforts, we can strive to create a school system that prioritizes the health and well-being of all its students, regardless of their medical needs.